Text

Kultur Regional

An eye for the picturesque and magical

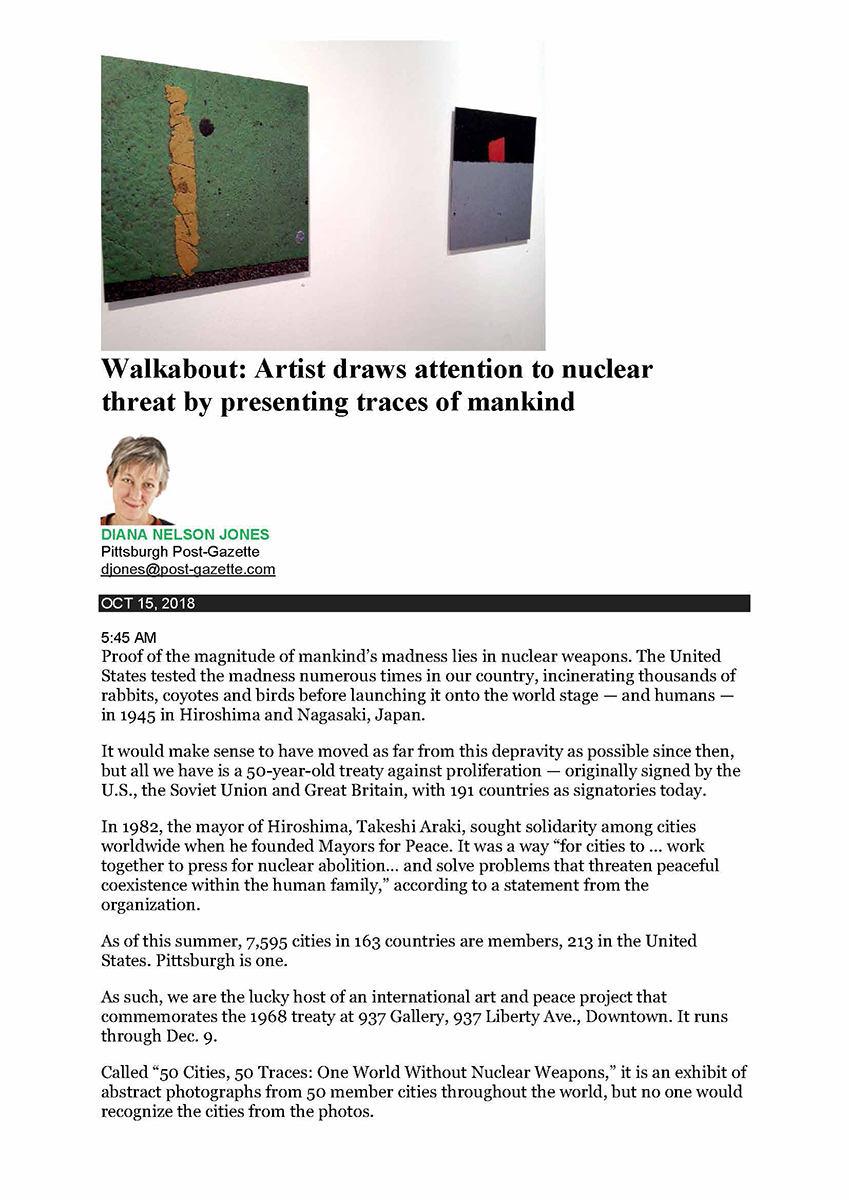

“Fleeting!” is the moment when Klaudia Dietewich captures her travel impressions. But the effect of her images lasts a long time. Some snapshots mutate into paintings, others into cryptic symbols. The “trace seeker” displays her astonishing finds at Galerie M in Landau.

By Brigitte Schmalenberg (Die RHEINPFALZ Speyerer Rundschau – Nr. 264, Friday, November 14 2025)

It all began with a bike tour from Lisbon to Warsaw. “When you sit on a bike all day and look at the road, you see a lot of asphalt,” says Klaudia Dietewich from Stuttgart, describing the break she took with her husband 15 years ago, which set her life on a new course. After that, she quit her job as a social education worker and became a “trace seeker.”

With a simple digital camera, she has been “snapping” everything that catches her eye and is inconspicuous enough to sharpen her gaze. On the bike tour, these were markings on the center strip, guard rails, gasoline stains, cracks in the tar surface, manhole covers. Back in her home town of Stuttgart, she began evaluating her collection, which was actually where the work really began. She had to sift through the material, sort it, and find the decisive sections for XXL enlargements. “My goal was to create a good image,” says Dietewich succinctly. So good that she herself enjoys looking at it, that it fascinates others and inspires multiple associations.

The result is hundreds of “road pieces,” all in the same square format, which means they can be rearranged again and again. The painterly effect of the completely unedited enlarged sections stems from the motif itself, but also from the sophisticated printing technique on aluminum, which the artist worked on extensively with the printing workshop. The key is that the paint is applied in droplets, causing it to burst on the finely corrugated surface, which creates a plastic effect.

The fact that the “street scenes” became more and more colorful in the course of her travels has to do with the streets themselves. “The road markings and landmarks also became more and more colorful.” It is all the more astonishing that the “landscape pictures” taken in Antarctica, which actually capture wide views of snow-capped mountains and seas of fog, look like old sepia photographs. The striking red tones that stretch across a snowy surface and almost took the tracker's breath away with their magical, surreal appearance are algae that she would never have expected to find in this area. And then there are pictures that look like landscape paintings from the Italian Romantic period, but were actually taken on a beach in Brittany. As with her street photos, the globetrotter, born in 1959, focused on the traces of waves and plants in the sand and turned the snapshots into enlarged details with prints on paper.

“These pictures were painted by the sea, so to speak, when the tide came back in,” she says, describing the decisive moment when she pressed the shutter button. The result looks as if the viewer has zoomed into a fairytale-like, forested primeval world that no one has ever entered before. Or—such fantasies also come to life—like a dystopian landscape of rubble that one would rather stay away from.

“I come from a painterly background, and I try to translate that into my photos,” explains the artist, who has always painted and also enjoyed working with screen printing. However, she prefers not to be referred to as a photographer. “I never learned this craft and I just snap away,” using the automatic mode of her small digital camera, without editing the images on a computer. But with a very special eye for the picturesque and magical.

DIE AUSSTELLUNG

„Flüchtig!“ Fotografie von Klaudia Dietrich bis 19. Dezember in der Galerie M am Deutschen Tor Landau: Fr/Sa 15-18 Uhr sowie nach Vereinbarung. Vernissage 14. November, 19 Uhr.

Klaudia Dietewich

Fleeting

Einführung: Helmut Anton Zirkelbach

Landau in der Pfalz, Galerie M, 14. November 2025, 19:00 Uhr

It is a special honor for me to guide you through the work of Klaudia Dietewich today. At the heart of her artistic practice, which has been growing for two decades, is a persistent search for traces: she explores the fleeting and transitory—those subtle signs that humans and nature, as equally creative forces, engrave into the world.

Let us journey together through the various series in this exhibition, which impressively demonstrate Dietewich's characteristic approach and her artistic development.

Let us begin with the “Wegstücke” (Pieces of the Way), an ongoing project that has been documenting the skin of our cities for many years and, in a sense, forms the foundation of Dietewich's artistic cosmos. The strict form of the 50 x 50 cm aluminum composite square manifests a conceptual stringency that operates without spatial or temporal limits. The images hung here in blocks form a global network, so to speak. They show traces from cities nearby and around the world—all accessible from Stuttgart Airport. The fact that the photographs were taken over several years proves that the artist works with great consistency and perseverance.

What we see in these “Wegstücke” (pieces of the journey) is a polyphonic diary of being on the move: a black sun over Berlin, a floating, bizarre rubber figure over Helsinki, a belching chimney in Budapest. The Eiffel Tower appears, the setting sun in Venice already seems seasick. One could read a lot into these images – and yet they resist any hasty attempts at interpretation. They remain free of any narrative ballast. Here, Vienna's Ringstrasse has fallen apart, there a black and silver cross beckons from Kreuzberg, New York dissolves into a structureless depth.

The artist herself, however, retains a precise memory of the place: she knows which “travel sketch” was created where, what, and when. Her informal, spontaneous gaze gives rise to profound images whose photographic pigment prints on matt-gloss Aludibond appear differentiated – between glazed delicacy and impasto heaviness. These image fragments awaken in the viewer a longing for the mysteries of nature, for elemental power and ambivalent impenetrability. Again and again, one discovers something new: organic forms, truncated characters, splashes of color—traces that the next rain may have already washed away.

This is followed by the series “Metalimnion,” which explores those fascinating border areas between order and chaos, between high culture and everyday life. The title refers to a thermal jump layer in bodies of water—a border zone that separates different worlds. It is precisely these intermediate spaces that Dietewich examines in her large-format photographs, which shimmer in greenish-cloudy tones.

What at first glance appears to be a mysterious underwater world—greenish-turquoise surfaces reminiscent of floating algae, primeval fossils, or microscopic organisms—turns out to be something completely different upon closer inspection: they are traces of skateboards, skid marks, dirt, and adhesive residue on the greenish-transparent skylights of the art museum on Kleiner Schlossplatz in Stuttgart. This is where the fascinating paradox of the series unfolds: down in the museum, the strict rules of art apply. But up on the glass panes, the chaos of everyday life reigns supreme – with chewing gum, skid marks, and fingerprints.

Dietewich documents these fleeting interventions and transforms them into enigmatic, aesthetic cosmoses through her photographic perspective. She deliberately leads us astray, only to confront us with the realization that the magic of the image remains independent of its mundane origin. Change and even destruction thus become the basis of a new beauty. You don't need to know that these are chewing gum residues to immerse yourself in this greenish space. But once you know, the series calls everything into question: our way of looking at things, the definition of art, and the hierarchy between high-culture locations and everyday traces.

Metalimnion becomes a metaphor for the layer between illusion and reality—and for the fact that the decisive signs are often found precisely where no one else looks.

With the “Red Dots,” Dietewich pursues a particularly concentrated form of searching for traces. The series was created in 2010, immediately after the opening of Tempelhofer Feld in Berlin. In her search for traces of the new public life, she discovered a seemingly banal peculiarity: red dots in the asphalt. Twenty of these motifs are placed here in strict sequence. Printed on thick handmade paper, each image takes on the haptic presence of a document.

But the initial uniformity proves to be deceptive. No dot is perfectly round, hardly any are pure red. Instead, subtle differences reveal themselves: a black spatter here, a gray line there, a dark cross above the “glowing sun.” The question of origin—skid marks, sneakers, skateboards—deliberately loses its significance. What is decisive is the transformation into pure graphics: the intense pink-vermilion color, the central arrangement. The repetitive yet always unique “sun circle” becomes an accumulation of energy.

This is typical Dietewich: she digs in and takes a close look! While red dots in the art world solemnly proclaim “Sold!”, she presents us with a whole armada of such dots – which are anything but tame. Her dots are wild, playful and completely unsellable. So while the gallery dot celebrates a business deal, her dots tell stories of fleeting moments and pure life energy. A clever and humorous side swipe at the art world.

Das ist typisch Dietewich: Sie beißt sich fest und sieht genau hin! Während rote Punkte im Kunstbetrieb feierlich „Verkauft!“ verkünden, präsentiert sie uns eine ganze Armada solcher Punkte – die aber alles andere als gezähmt sind. Ihre Punkte sind wild, verspielt und komplett unverkäuflich. Während der Galerie-Punkt also einen Business-Deal feiert, erzählen ihre Punkte Geschichten von flüchtigen Momenten und purer Lebensenergie. Ein cleverer und humorvoller Seitenhieb auf den Kunstbetrieb.

And the location, Tempelhofer Feld, makes it even more ironic: on this

historic ground, once a symbol of progress, she captures the traces of today – the random, ephemeral works of art of everyday life. In this way, she continues the monumental history of this place with the subtle, poetic stories of our present. The series “Fleeting Landscapes” marks a turning point in Dietewich's work toward exploring natural elements. This multi-part work is dedicated to the traces in the sand, the fleeting formations created by water and wind on beaches and coasts, only to be erased again in the next moment. Dietewich's camera becomes a witness to that brief moment when the tides, the wind, and gravity combine to create patterns—patterns that appear for a fleeting moment like finished compositions.

These photographs create miniature landscapes. We can read entire topographies from the macroscopic images of the sand surface: we see fjord-like branches where the water has receded, delta-like structures, and wave-like ripples reminiscent of dune fields in the desert. With great sensitivity, Dietewich also captures delicate, almost floral forms, where algae residues or foam write themselves into the sand like tendrils and blossoms. These are states of utmost transience, documented in the knowledge that the next wave, the next gust of wind, will change everything again, erase it and start anew.

In a reduced, almost monochrome color palette of sand, beige, light brown, ocher, and subtle gray, the viewer's gaze focuses entirely on the essentials: form, texture, light. This reveals to the viewer the primal forms of nature—abstract compositions reminiscent of archaic maps or microscopic images of lifelines. The formal presentation of this series impressively underscores its conceptual approach.

The individual works are laid out in landscape format, which logically emphasizes the vastness and horizontality of the landscape. The “Fleeting Landscapes” series unfolds its full effect in a series of four to five images. This linear hanging creates a visual narrative that invites close viewing. One is invited to follow the subtle variations, the rhythmic changes, and the subtle progression of the forms—like the pages of a diary that records the fleeting traces of wind and water.

In “Vanishing Universe,” Dietewich continues her exploration of natural signs and hieroglyphs, leading us even deeper into abstract Antarctic worlds reminiscent of microscopic organisms or cosmic nebulae. Here, her search for the essential formal language of the ephemeral condenses into a universal visual language that encompasses both the smallest and the largest. The series becomes a meditation on the cycles of creation and decay that run through the entire universe.

Our journey through Dietewich's work concludes with the series “Torshavn” or “Faroe Islands,” which translates the essential topography of this island group into an immediate, haptic visual language. The focus is not on postcard-like landscape photographs, but on the rough, scarred surfaces of the island itself: the tracks left by vehicles on the roadside. In a reduced, powerful palette of gray and black, the artist captures the profoundly transitory and at the same time eternal nature of this North Atlantic landscape.

In these close-ups, mountains of asphalt and rock pile up, seemingly overnight new mountain ranges emerge from torn-up material, only to collapse again in the next image. What we see are the scars of the elements and the traces of use: deep cracks in the ground, asphalt splinters, and the texture of rock that has been pressed by ice and wind over thousands of years. These close-ups, reminiscent of abstract painting, tell a multi-layered story. They are both map and territory. The fine ramifications of the cracks trace the fjord-riddled coastline of the islands; the rough, dark areas evoke the basalt cliffs.

Dietewich gelingt es damit erneut, das vermeintlich Bedeutungslose und Übersehene – den Staub, den Riss, die Schramme – zu einem poetischen Zeugnis eines Ortes zu erheben. Die Serie „Torshavn“ ist keine Beschreibung der Landschaft von außen, sondern eine Innenschau. Sie lädt uns ein, die Inseln

Dietewich thus succeeds once again in elevating the seemingly meaningless and overlooked—the dust, the crack, the scratch—to a poetic testimony of a place. The “Torshavn” series is not a description of the landscape from the outside, but an introspection. It invites us to understand the islands not through the eyes of an observer, but through the skin of their own surfaces, in a constant geological transformation.

Development

Looking at Dietewich's artistic development as a whole, it takes place in a fascinating reversal of conventional expectations: her search for traces began with the series “Wegstücke” (Pieces of the Way). Here, she focused her attention early on the man-made traces in urban space – on the archaeology of everyday life, inscribed in asphalt and on walls. These works read the skin of civilization like an open book and elevate the unintentional poetry of our legacies to the status of something worthy of contemplation.

Only later, in series such as “Vanishing Universe” and “Fleeting Landscapes,” did the artist expand her investigation to include the traces, signs, and patterns of nature itself. From the asphalted city ground, she turned to the dunes by the sea, from the scars of civilization to the hieroglyphs of wind and water. This reverse chronology is of great significance: it shows that Dietewich's artistic method—learning to see in the seemingly insignificant—did not begin in untouched nature, but right at our feet in the everyday world. Her path did not lead from the vastness of the landscape to the confines of the city, but exactly the opposite: from the microcosm of urban signs to the macrocosmic lettering of natural elements.

Her work thus proves to be a consistent expansion of the field of perception. What began in the “Wegstücke” as an exploration of the immediately human found its universal counterpart in the “Fleeting Landscapes.” Together, the two series form a comprehensive cartography of transience—a search for the essential formal language that runs through everything visible, whether created by human hands or shaped by the elements.

Twenty years ago, I met Klaudia Dietewich and her husband Raimund – since then, I have been following a career path that led from screen printing to photography and culminated in an unmistakable artistic signature. Born in Freudenberg and a long-time resident of Stuttgart, the artist has had an unusual career path: after studying social pedagogy and working in the field, she discovered art between 1999 and 2007 at the European Academy of Trier – first screen printing, then rapidly moving on to photography.

Dietewich has always been a traveling artist, whether by bicycle, car, or plane. This constant traveling, collecting wondrous pieces of road and asphalt with her camera, seeking out hidden fractures and beauty—this has become her trademark. What began as an artistic quest has matured into an unmistakable visual language. Numerous exhibitions worldwide and acquisitions by collections and museums attest to this.

We all want to leave our mark, connected with a deep longing for authenticity. This longing for the impossible, for passion, for the power to influence the course of events – all this is condensed in the work of Klaudia Dietewich. Together with her partner Raimund, she has transformed this longing into tremendous artistic power. A power that challenges, surprises, and deeply impresses us time and again.

Her work invites us to see the world with new eyes—as a living archive of fleeting moments that gain a lasting, poetic presence in her art.

Thank you very much for your attention.

Vielen Dank für Ihre Aufmerksamkeit.

Klaudia Dietewich

Fleeting Landscapes - Photography

Henner Grube

Waiblingen, Neuer Kunstverlag, Feb. 13 2025

The waves come. The waves go. Something remains.

The artistic process requires time. A rich, diverse and developed background of experiences promotes inspiration and can create something that was not there before. The artist opens up new areas of experience and perspectives on the background of traditions. However, the models, even the archetypes of art, lie in nature and in the midst of life. The result combines the old with the new.

Klaudia Dietewich and her husband, Raimund Menges, travel around the world. By plane, by ship ...

Last year, Klaudia Dietewich published a book with photos of the Antarctic here at Neue Kunstverlag, Waiblingen: “Vanishing Universe”. White patches of snow. Uneven. Glacier fields. Lava-black features of mountains and hills. Occasional aspects of the sea coast. A hazy, icy atmosphere. Inhospitable. Deserted, away from civilization. Apocalyptic visions are awakened ... Perhaps the disappearance of the world. On the other hand: a sublime, magnificent, self-contained world.

Klaudia and Raimund are traveling. They travel by bike. They walk. What does Klaudia bring with her?

The artist Klaudia Dietewich started out with screen prints, but she has long been known for her photographic works.

Over the years, she has presented a very large number of photos in the “Wegstücke” series, which mainly show sections of the pavement of streets, paths and squares, but occasionally also of walls, cities and landscapes, industrial plants and other building complexes. Cracked parts of surfaces can be seen, changes due to weathering, repairs, skid marks, colored markings for repairs, geodesic markings, stains from paint residues, edges of water and oil stains, chalk marks, paste-overs, scraps of writing ...

The photos are reminiscent of representational or abstract motifs of fine art, sometimes organic, sometimes informal and expressive, sometimes constructivist and geometric ... Sometimes they evoke associations with terrain or stick figures. Bears, amoebas, trees, bushes seem to be visible. Other figurations look like rain, shadows, others like sketches or signets ... A fascinating abundance.

The photographs for this series were taken in Europe, America and Asia. The artist always has her digital camera with her when she rides her bike or strolls through cities. She never takes her eyes off the ground. She pulls out the camera and takes pictures.

Klaudia makes a selection on the computer, determines the photographic detail; otherwise nothing is changed, no color, no design. In this “Wegstücke” series, the theme is not the sublime, but the inconspicuous.

Klaudia loves the “wabi sabi”, one of the classic Japanese aesthetic ideals. It is associated with the tea path and with architecture, ceramics, garden art and calligraphy. It realizes a beauty that lies in simplicity and naturalness. The things shaped by Wabi Sabi are rather asymmetrical, rough, irregular, earthy, characterized by traces of use, wear and tear, decay. Perfection, even magnificence, splendor or external pleasingness are not sought. The ordinary, the simple, the familiar, the everyday is embraced in an unaffected and unobtrusive way. Artistic objectivity is paired with deep contemplation of transience and a holistic view of the world.

We humans come and go. What remains when man has left the earth?

Klaudia's latest pictures are the subject of the latest catalog, the latest book here at Neuer Kunstverlag: “Fleeting Landscapes. Fleeting Landscapes”.

Schematic, almost monochrome pictures are shown. First of all, landscapes in landscape format on two adjacent pages, landscapes whose ground formations are reminiscent of Antarctic paintings. Several landscapes are slightly undulating, others somewhat more hilly. Occasionally, however, there are patches of vegetation or individual broken trees in these landforms. Then in portrait format, again over two pages, details from such landscapes: organic forms, plants, herbs, individual tufts, sometimes moving in the wind, sometimes rising straight up. Here you might recognize flames, there you might even suspect eruptions ...

Photographically captured here are ... phenomena in the sand. Klaudia Dietewich discovered the phenomena for herself and for us on a beach in Brittany. There are small black lava sequins in the sand of the beach. The waves of the strong tidal current take sand and lava particles with them. The lighter black particles sail over the heavier sand, are deposited and pass through it. New patterns emerge with each wave. They persist for brief moments until a new wave arrives. Delicate ...

fleeting existence. Empiricism of the moment. A constant change. Everything is in flux, seemingly comes out of nowhere, is wiped away, new things emerge ...

Klaudia Dietewich gains new impressions and aspects from the place she is in ... She does not shy away from grand views and gestures. However, she does not follow traditional narratives and atmospheric descriptions, but perceives poetic details, tracing them, collecting them. Regardless of whether it is on the road, on the wall or on the beach. Regardless of whether it is areas of our everyday culture or nature. The artist pays attention to the magnificent as well as the seemingly insignificant, often overlooked and imperfect. With her pictures she emphasizes the remarkable. She shows transitions between states, between art and nature, environment and life.

Waves come. Waves go. Klaudia and Raimund travel. Klaudia, what will you discover next for yourself and us?

Artistic work is almost tireless. Art begins with attention, curiosity, amazement, joy, enthusiasm, lust for life and love. Diverse energies are recognizable, forces that move and stir. The forms, colors, perspectives and horizons of works of art transform the viewer's views, attitudes and life circumstances when communicated successfully. All this remains. As long as there are people, this searching, desiring, shaping, this irrepressible erotic spirit of human nature ... and culture will remain.

Let's enjoy Klaudia's photos and books!

Our thanks go to you, Klaudia, and the Neue Kunstverlag! Good luck!

Introduction

to the book launch and exhibition “Vanishing Universe“

Photographs by Klaudia Dietewich

Neuer Kunstverein und Galerie, 71332 Waiblingen

February 1st. 2024

When I was first confronted with a selection from Klaudia Dietewich's Vanishing Universe group of works in an exhibition (Kunstbezirk im Gustav-Siegle-Haus, Stuttgart, 2023) some time ago, I was told by the artist that it was a series of photographic works based on impressions from a journey through the Antarctic. In my direct encounter with these works, however, it was surprisingly irrelevant to me at first which artistic technique they were actually executed in and which subjects or topographical details they might concern.

The ephemeral effect of the series of "pictures" shown there - pictures understood in a broader sense as pictorial experiences of the world around us - suddenly lifted themselves from the meter-high, heavy walls of the bulky exhibition space. Like photographs, they could just as easily have been paintings, with the melting of nuanced, overlapping glazes of color. Or drawings in the finely differentiated interplay of light and shadow. Or perhaps printmaking sheets, such as those of an accomplished sculptor, whose multifaceted surface structures reflect the tangible physical working processes on the underlying plates and sticks.

Klaudia Dietewich's current publication Vanishing Universe captures the immediacy and impact of these photographic works in a remarkable way. Even when viewed from a distance, it does not present itself as a glossy, lifestyle photo book - the title alone on the cover disappears into an atmospheric expanse or almost invisibly towards the bottom edge. And in spite of the cool, congealing colors of the images of water, snow, ice, rock and stone, it feels pleasantly soft in the hand as you leaf through it, making it clear that what we associate with the sensations of a seemingly inhospitable habitat is connected through and through with our own existence - and thus our survival.

These images of a vanishing universe - by no means gradually, but at breakneck speed - do not come from another planet, but entirely from this world. However, Klaudia Dietewich's photographic series captures the destruction of pristine nature as the existential basis of human life in a rather quietly observant way, without any superficial claim to climate policy protest. Instead, her exploratory journey through the Antarctic resulted in photographs that oscillate between reality as seen on the one hand and what is considered completely unreal on the other. Paradoxically, the powerful elemental forces of nature thus appear to be in the process of losing their own powers, caused by the ongoing environmental pollution. A deep astonishment sets in in the face of these primeval natural landscapes and, at the same time, a disbelieving amazement at their accelerated wastage and disappearance due to our behavior.

Klaudia Dietewich has repeatedly collected road signs - such as random cracks in the asphalt, road markings, traces of car tires, etc. - on extensive photographic work groups. Focused close-up on baryta prints or on aluminum dibond, they also resemble abstract painting compositions or gestural drawings. However, whereas these works were man-made traces of markings that were spread across the ground - often by means of technical devices - in the Vanishing Universe series, nature itself "draws" (and is painfully marked by human misconduct). No longer successively accumulating layers, but year after year, day after day - in the opposite direction - irretrievably eroding sediment after sediment, the earth thus reveals the inner face(s) of its past for a brief moment in the photograph.

Between two poles, Arctic and Antarctic - sea surrounded by land, land surrounded by sea - in the midst of the once assumed eternity of ice and an unstoppable disappearance: The lava-black land masses rise up out of the snowfields like pale dream shapes, fine-edged silhouettes on the towering mountain peaks that crumble downwards into a soft white, both the sea below and the sky above calmly restrained expanses. Rotalike lights glow from beneath the huge ice shelves, a threatened and menacing no man's land opens up before us - that inner glow in which millions of years of hidden plant life is unexpectedly possible, which could easily have managed without humans.

Clemens Ottnad

Introduction

to the exhibition "regarde

Photographs by Klaudia Dietewich

Orangerie im Hofgarten, 74592 Kirchberg/Jagst

Sunday, September 11th, 2022

Have you ever been out and about in nature after a rain shower, out and about in the city, no matter where, whether in the deepest forest or in a winding backyard between grey house walls, you move towards a puddle and from a certain angle the sky is reflected in it? It's a spectacle every time, it's touching every time and somehow it's also a great comfort to see the sky in a puddle and even children know that if you make yourself small in front of the puddle, you see more of the sky.

And when we walk towards the Orangerie here in the Hofgarten, when we approach the exhibition building, we see the two-part work 'regarde le ciel' by the artist Klaudia Dietewich, and indeed not only the trees and bushes are reflected, but also the sky is reflected by the window panes of the Orangerie. Presumably, the quickly sprayed graffiti was on the ground, somewhere in Paris, and the attentive artist captured it with her camera.

Since Klaudia Dietewich gave up her work as a social worker many years ago, since she stopped painting and drawing and also silk-screen printing completely, since then she has created an artistic photographic oeuvre, the significance of which is now becoming more and more apparent, as it has continuously developed away from common fashions.

Die Künstlerin fotografiert Spuren, sie hält ihre Kamera, wo sie geht und steht auf den Erdboden, sie fotografiert Straßenstücke und Löcher und Schrammen im Gehweg, ihr Interesse gilt den Verletzungen der Straße, dem schadhaften und geflickten Asphaltstück, nicht dem Makellosen, so bildet das rissige Asphaltstück am Straßenrand den Nährboden für Kunst. Die Künstlerin findet das Aufregende und Bemerkenswerte in ihrer urbanen und nächsten Umgebung an der Bordsteinkante in Stuttgart Degerloch, genauso wie im weitentfernten rissigen Mauerstück in Shanghai.

Nowadays, it is precisely the smooth and flawless that is the signature of the present and I ask myself why is it that we find the smooth so beautiful?

It embodies today's positive attitude, especially with our super-smooth smartphones we follow the aesthetics of the smooth, not only externally, but also in terms of content, any kind of communication seems smoothed out, only positive likes are valid, a dislike - I don't like it at all - no longer exists in the world of influencers on Instagram. Sharing and liking are a means of smoothing out communication, negatives are eliminated because they represent obstacles for our accelerated communication.

Once discovered and photographed, they are sorted and catalogued on the computer at home. The artist meticulously records the place, time and date for each of these photographic objects and, after printing them on aluminium-dibond panels, labels them in detail along with her signature on the back.

So the artist always carefully chooses the material, chooses the detail.

She selects the composed detail, which functions according to the laws of her art, in such a way that colour and form are in harmony and in tension with each other. Long phases of work of great intensity precede the panels that appear so light, hours and days of selecting and encircling the motifs.

Seeing - thinking - deciding.

And thus Klaudia Dietewich turns an incidental occurrence that lies beneath us, on the street and under our feet into a picture and a work of art.

And what can't all be discovered on the path, which is divided into several small groups. A fragile yellow stripe with a black determined dot on a green roughened background from Pittsburgh, a rising small atomic cloud from Nagasaki, a five-part bush of feathers from Oldenburg in front of a blue geometric background, an overturned shapeless table from Istanbul on a dark red carpet, a wonderful yellow sock from Buenos Aires, a black blob with small friends from Tokyo and a hanging branch from Wissembourg in France with a last leaf on it. A little angel beckons from Würzburg and the Leaning Tower of Pisa is now in Paris.

You see, it is easy to read a lot into things without giving them any real meaning or nonsense.

These signs do not point to anything. They stand for themselves and are free. And yet they stimulate my imagination, and do so even more when I learn where these wondrous road signs and asphalt drawings come from and how universal they ultimately are!

Red dots

In the art world, red dots stand for a sale, so red dots stand for success, if you will, for a success of the artist or the gallerist. Years ago I was at an art fair and for 5 days I watched the goings-on in the gallery booths across the way.

The week went by sluggishly, was exhausting and sales, both in my own and neighbouring berths were sluggish and left a lot to be desired.

But on Sunday evening, it must have been after 5pm, something amazing happened. I was watching the two pretty girls from the well-known Visasvis Gallery and they were busy sticking red dots on almost all the paintings on display.

I rushed over to congratulate them and was delighted to see the flood of red dots, ............the two girls just grinned and one of them said in a friendly way that the boss had just called and ordered them to stick red dots....

Irritated and disappointed, I went back knowing that I was in kindergarten.

This little, rather laughable episode has nothing to do with the work of Klaudia Dietewich, it only shows that lies and deception and a lot of hot air are part of daily business in the art market, as everywhere else.

Immediately after the Tempelhofer Feld in Berlin was opened to the public in 2010, the artist travelled there to take photographs, presumably she sighted a lot, discovered a lot and photographed even more. Among them, a whole series of Red Dots, 20 of which she placed on the front wall of this room and hanging around the corner. Printed on especially thick handmade paper, all the red dots look different, they are never equally round and hardly any of them are pure red, here a black dot at 6 o'clock, there a grey line at half eight, here a dark cross 3/ 4 five and here one across the glowing sun.

Woher die Spuren kommen mögen, spielt gar keine Rolle mehr, ob von Bremsspuren eines Fahrrads oder von Turnschuhen, von Skateboards oder Dreirädern, das ist ganz egal, entscheidend ist nur ihre grafische Wirkung, ihre Zinnoberrote Farbe, ihre immergleiche Anordnung, mittig auf dem starken Bütten, der sich wiederholende Sonnenkreis, sich immer anders wiederholend ist es ein Ansammlung von Kraft und Energie, das ist der Stil der Künstlerin, an einer Sache dran zu bleiben, genau zu sehen und uns damit zu konfrontieren, einer Sache auf den Grund gehen, wieder und wieder, und uns fragend ob wir mitgehen auf die Suche nach den kleinen Unterschieden, ob wir mitgehen nach den reizvollen Entdeckungen im Rot und uns fragend was ein Bild oder eine Bildreihe kann? Was leisten die Farben? Was bewirken sie im Raum?

They give a lot to the conscious viewer and since they are located on a former airfield, an airfield that was meant to take off into the sky, they again fit so well with our initial view of the sky.

Metalimnion

I believe that some signs can only be found by Klaudia Dietewich, can only be discovered by her, or even more clearly, they only exist in order to be found by her!

With the series Metalimnion, the artist shows us once again that her photographs do not simply show a section of the visible world, of visible phenomena, but rather depict the visual traces of the time in which they were taken.

Metalimnion is the confusing and initially meaningless title of a series consisting of over 20 works, six of which the artist has brought here and spread out on the floor.

Metalimnion describes a kind of thermal thermocline......., the middle layer of a stagnant body of water that separates the upper, warmer layer from the lower, colder water layer, according to the explanatory view of the term on Wikipedia.

And indeed, we immediately believe ourselves to be in an underwater world, the greenish turquoise surfaces appearing like underwater photographs or deep cuts into the eternal ice. We think we recognise algae, small aquatic animals, amoebae and small fish, we believe we are undoubtedly underwater.

And in many a detail I think I recognise a primordial animal cast in synthetic resin, a winged insect, a primeval fossil, slowly drifting timelessly in the greenish turquoise colour space.

What we see in reality, however, is sobering and fascinating at the same time.

No living beings at all, but are simply dirt, skid marks, glue residues and much more, on a greenish transparent glass pane. These are the glass panes of the skylights of the Kunstmuseum at Kleiner Schlossplatz in Stuttgart.

You can't guess that, via the title, the artist leads us down a wrong path, whereby no one, without reading up, knows what Metalimnion means. Yet she leads us on ice, so to speak.

Is this important?

No and yes, maybe it's a joke she's making by selling us skid marks and chewing gum residue as primordial animals, or maybe she's questioning her art and, above all, our way of looking at it. I don't need to know that this is glue residue to be able to lose myself in this painting, to dive deep into this endless green space.

Art confronts us by being seen, by looking at art and at the world. By walking, driving and travelling I move through the world and by looking at art I move through the picture, or on the sculpture and yet always remain with myself. However, what I myself have in my luggage is also decisive when looking at art and discovering the world. So my question is What is there?

Ladies and gentlemen, what is there? This is the question I ask myself when I go to an exhibition. And with this question I try not to block anything for myself, but on the contrary I try to open myself, to open myself up and perhaps to let myself in for something unfamiliar. I DON'T ALWAYS SUCCEED.

Because just as the artist has a lot of things in his luggage before he starts working, I as a viewer have a lot of things with me as "head luggage", sometimes I'm in a good mood and sometimes I'm in a bad mood, or irritated and then everything is too much for me and all it takes is one unpleasant colour to make me furious, other times I am full of humour and smile about many things I see.

For example, in the work DESOBEISSANCE, which is leaning against the wall in the courtyard outside, I immediately have a direct reference to the shooting of the rebels by Francisco Goya, especially on this wall, which looks so brittle and scraped off, this writing of 'disobedient' seems to me like a contemporary answer to the picture of the great Spanish artist, whom I admire very much, painted in 1814. And disobedience, that is DESOBEISSANCE, is virtually a civic duty in times like these!

My little tour of the exhibition ends in the basement of the house, where the artist shows us two videos: On the one hand, we see the blue water

of a swimming pool, in which the light of the sky is refracted in endless waves, and again we look up at the sky although we point our heads downwards.

And on the other hand, we now see the sky over Degerloch projected here into the bricked-up window recess of this cellar room. If you listen carefully, you can hear a few children's voices and now and then a bird flies through the picture. With these two glimpses of the sky, the exhibition "regarde" comes full circle, as does our imaginary view into the puddle.

The artist's informal approach creates profound images. The sensitive photographic pigment print on the shiny metal is chosen in a very differentiated way and ranges from fine glazes to almost impasto heaviness.

The non-objective image sections can evoke in the viewer a longing for the riddles of nature, perhaps also for its power, the play of the elements or an ambivalent impenetrability. There is always something new to discover: organic forms, abbreviated characters, splashes of colour and traces that can disappear after the next rain.

We all want to leave traces and do so incessantly, partly linked to a great longing for authenticity.

This longing for what is actually impossible, for what many lack in their everyday lives - the passion - the determination to influence the course of things - the desire to be someone else, to transform oneself and set out for the land of miracles and surprises, all this and much more can certainly be found in the life of Klaudia Dietewich, but in teamwork with her partner Raimund she was and is able to transform this longing into tremendous power and it is precisely this power that we also find in her art. Which challenges, surprises and impresses me again and again.

Thank you very much.

Helm Zirkelbach

Spurenlese – The Relevance of Questing Traces

The poet, by carefully selecting his words and relying on his sense of rhythm and rhyme, extracts the quintessence from the banality of everyday language. Between the lines, his poem opens up an echo chamber in which to examine the meaning of life. In the same way, artist Klaudia Dietewich creates her densely suggestive extracts of reality by drawing from the unpretentious and the trivial, which she discovers in man-made habitats. Her keen eye perceives traces of wear and tear, vestiges of previous use, on road surfaces or building facades. In the seclusion of her laconic photographs, these images are transformed into skillfully composed works of abstract art – transcendent and elemental. A detail of superimposed lane markings on asphalt, for example, evokes suprematist concepts. The well-balanced, pure geometric composition calls to mind the energetic-intellectual absolutism in visual expression sought by the early 20th century avantgarde. Furthermore, Klaudia Dietewich's photographs of tar patches bear gestural lines that reference informalism. Scratch marks on facades evoke atmospheric landscapes, streaks of color resemble satellite images of the Earth’s surface, cracks in plaster suggest rivers and deltas.

The beauty of these omnipresent trifles lies in the eyes of the beholder. In reality, we are likely to be oblivious to them in the context of our everyday surroundings. However, thanks to the artist’s adept selection of motifs and subtle staging, we may be inspired to perceive these traces in our immediate environment with a fresh eye. Flaws and patches are no longer judged defects; instead, these markings enhance mundane surfaces. It is worthwhile to consider man-made traces: not only do these manifest the will to utility, but also natural coincidence. They are evidence of a society’s cultural characteristics, insofar as a comparison of traces from different cities, countries, continents allows us to draw conclusions about the respective aesthetic idiosyncracies and preferences. The often unintentional repairs in public places and the accidental traces resulting from mechanical influences through previous users are mute witnesses to a universal creative drive.

These public phenomena are transformed into works of art only through discovery, creative focus, and astute, complex staging. The artistic transformation of the trivial into a meaningful visual language amounts to the ennobling of normality. After observing Klaudia Dietewich’s staged extracts of reality, the beholder will experience familiar surroundings with new awareness. Attuned, armed with sharpened eyes, we will seek traces in familiar surroundings, gaining a new connection to what we previously ignored. The traces discovered and appropriated will become familiar, eventually subsumed into the diffuse feeling we refer to as “home.” They become parameters of the places where we carry out our daily tasks – and thus a part of our individually unspectactular lives.

From an art historical point of view, Klaudia Dietewich’s quest for traces and transformation draws on the avantgarde achievements of early modern and post-war art movements. At this time, various innovative artists had abandoned academic notions of art and begun to create works manifesting a new visual language involving unorthodox methods and materials previously held alien to artmaking. In Paris even before the First World War, artists such as Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Juan Gris, along with the Zurich Dadaists Hannah Höch, Kurt Schwitters, and others after 1916 integrated quotidian snippets into their collages and oil paintings. Between the wars, the prolific Max Ernst took up frottage, creating a fascinating body of work involving everyday objects and inconspicuous surfaces, heightened by the addition of skillful drawings to create surreal phantasms. From the mid-1950s, pop art pioneer Richard Hamilton focused on the power of the filtered image gleaned from the consumer world with his collages incorporating contemporary advertisement. In the 1960s, the artists of the Parisian nouveau réalisme practiced the direct and provocative application of found objects and traces in their art. In particular, Jean Tinguely with his métamatics, Jacques Villeglé with his décollages and déchirages, and Arman and Daniel Spoerri with their accumulations und assemblages subversively questioned the traditional idea of individual artistic process, causing a furore with their notorious artistic actions. In addition, land art focuses particularly on the fascinating subject of traces. Here, natural phenomena may be concentrated through artistic intervention (Andy Goldsworthy), or the artists themselves either create traces in situ (Michael Heizer, Richard Long, Robert Smithson) or document their temporary presence through concrete material, acoustic, or verbal-imaginary tracks (Lothar Baumgarten, Hamish Fulton). Later, artistic extracts are made accessible to a broad public through exhibitions. Klaudia Dietewich’s oeuvre dovetails with this canon of avantgarde trackers and transformers, offering a new and versatile approach to the artistic appropriation and processing of traces.

Dr. Gabrielle Obrist, Zürich, 2016

Statt Ansichten - Exhibition Series STADT/LAND/SCHAFT

Galerie im Kornhaus, Kunstverein Schwäbisch Gmünd e. V. – 7. Nov 2014

Accompanying the State Garden Show 2014 of the city of Schwäbisch Gmünd, the Kunstverein Schwäbisch Gmünd explored the concepts of city and garden in a series of exhibitions. We assumed that a garden is a demarcated piece of land, privately used for growing crops or also for artistic, spiritual or therapeutic purposes. A garden does not correspond to nature. It is always artificially created, controlled; it is tamed, shaped and cultivated nature. It condenses plants and landscape forms in a limited space, i.e. it is a designed image.

Cities, we have come to think of them, are also firmly delimited settlements, condensed cultural spaces in which people live in specific social and spatial organisations. The urban landscape (urbanscape) resembles the concept of the garden in its planned, but often also uncontrolled growing and overlapping spaces and networks of relationships in connection with controlled urban planning and administrative organisational structures.

So in the exhibition series STADT/LAND/SCHAFT we have traced the structures of landscape and urbanscape, taking into account diverse natural, cultural and social aspects. I highly recommend the catalogue with all the participating artists as well as texts and reflections on the theme.

The Garden Show is over, we have one last exciting contribution to offer.

Klaudia Dietewich's STATT ANSICHTEN.

All nature, all references to the plant world, to growth, as they still sounded in the previous exhibition by Hannelore Weitbrecht, are now completely removed. We see a lot of grey, shiny metal in front of us. Square or rectangular plates seem to float a little in front of the wall, oscillating between pictorial and object character, arranged in groups. In a floor work, uniform blocks are in a strict, linear row. On the wall hang objects, found objects, that can hardly be traced back to their original meaning and origin. And scenes from the underground stations of the world's metropolises are shown on a monitor.

The works exhibited here, with their reduced colour palette and geometric rigour of arrangement and grouping of formats, already offer a very superficially appealing charm in the sometimes dominant medieval space with its heavy, dark brown oak pillars and the many mullioned windows. Thus attracted by the whole ensemble, we as viewers then next try to find out what we are actually seeing here. It was difficult for me to press my thoughts on this into a stringent order. I would therefore like to share with you my reflections and associations on individual keywords that I think are related to this exhibition:

Trace

How do we know that there was once a sea of snail-shaped creatures, the ammonites, in our area? There is nothing left of most of the ammonites that we find as fossils in the slates, for example from Holzmaden, the parts of the body and shell were completely compressed. However, this happened in soft mud that only later hardened into stone. So what we still see of the animal here is not its body, but the imprint, the trace that this body left in the mud. The term trace originally only refers to the footprint. If you watch the Sunday detective stories on television as avidly as I do, you will immediately think of all traces that reveal the presence of people and possibly also the course of events.

Klaudia Dietewich collects traces. Not with a criminalistic flair but as an artistic method. What you see here on the walls and floor were initially photographic detail shots of inconspicuous, perhaps run-down places. Road markings, oil stains, repairs in the road surface, dirt. When someone arrived at the Gmünd bus station lately, their gaze certainly rarely fell on yellow markings in the asphalt. I, for one, did not notice these markings in the hustle and bustle of the garden show or its preparation last year. The work, which can also be seen on the invitation card, was created in October 2013. Klaudia Dietewich seems to be tracing motifs in a city that most people pass by carelessly, possibly even rejecting them as ugly spots. She thus shows us in this exhibition STATT ANSICHTEN, which is the title of the exhibition.

View, then, is the next keyword.

A view is first of all an illustration, depiction, representation. In other words, it is actually a picture. Already here an ambiguity creeps in, which we will encounter further in the works of Klaudia Dietewich. An ambiguity that is ultimately also absolutely necessary. "If a work is unambiguous, it is not a work of art", was the thesis of my former teacher Professor Paul* Kästner in Heidelberg.

Of course, we also know view in the meaning of aspect or opinion. The concrete standpoint of a viewer in a visual experience then became a position in the abstract, cognitive, psychological sense. And view is also perception, both in the sense of conception, perception, and in the sense of an assumption. The direct cognition of sensual objects can also be understood as an inner view, as a direct grasp of mental states and processes.

Klaudia Dietewich, we can therefore assume, takes visual phenomena as an occasion to take a position, a standpoint and to communicate her view of the world. This brings us to Statt (not meaning “City” (Stadt) but “instead”) with double T in the title of the exhibition. It is not only the city, the urban landscape that is always the motif here, that is in the foreground. Behind this play on words is also the desire for a different view, a change of perspective, a point of view that leaves the usual paths.

Which brings us to the next keyword:

Way

Spur also has the meaning of lane. Even here, again with a strong regional reference: in hardly any other city in the vicinity can we currently see more clearly what happens when traffic is forced to constantly look for new lanes. The flow of traffic comes to a standstill, the road becomes an ordeal. And in this reorientation and slowing down, we possibly also perceive the way again in its peculiarity. Way comes from move, meaning a strip in the landscape along which one moves from one place to another. To the keyword path we could also add the keywords movement and journey.

The floor work in this exhibition marks such a path. What looks like the speed of a take-off or landing runway, reduced to a linear order, is actually the result of months of travelling. Klaudia Dietewich cycled around half of Europe, from England via Scandinavia to the Black Sea. It is the slowness of this journey that enables her to see the inconspicuous details that serve here as representatives of all these places, streets and cities. Traces from many places mark a long journey. Movement is also a theme of the video work you see here. Movement, in movement also encounters and at times rudiments of communication. Everything is filmed from a distanced, almost voyeuristic point of view, like a spy or surveillance camera, which virtually forces you to change your view, to change the view you are used to from film aesthetics or from the consciously directed gaze.

Are Klaudia Dietewich's works, in their enigmatic foreshortening, signs?

Sign

A sign always stands for something else. It is something that can be seen or heard, that is intended as a reference, that serves to make something recognisable, that is linked to a meaning.

However, we can also open up this exhibition for ourselves if we know nothing of all these references and connections. All these works always have an effect, and I already emphasised this at the beginning, through their aesthetic appeal alone.

This brings us to the last keyword:

Composition

Regardless of the technical execution, the photographs transferred to aluminium plates by means of pigment printing, which creates this specific metallic sheen, the actual artistic work of Klaudia Dietewich, apart from the conceptual development inherent in the motifs and their presentation, consists in the selection of image details and their arrangement. Here, the objects on the wall and floor ultimately do not differ from painting in their principles of composition. The weighting of the individual pictorial elements, the dynamics or statics of the directions in the pictorial objects, the use of colours, which gain in importance precisely in their reduction - so much so that a yellow found object measuring just 30 cm was tried out in all possible places during the construction of the exhibition, only to be finally taken down again because its effect was too dominant - these formal design elements form the actual framework on which the contents, which I have pursued somewhat associatively in my explanations, are securely supported.

Klaus Ripper

Ocular Alphabets, or

Hunting the Unheeded

Emblems, logos, and pictographs flank our daily urban life. Abbreviated, easily comprehensible symbols, their purpose is to help travelers – usually motorized – reach their destinations as efficiently as possible. With apparent reliability, the automatic trip planner or other navigator takes us to our destinations, even if we don’t understand the individual symbols in the jungle of signs. Self-optimized, our heads held high, we move through an ever more streamlined world like an arrow, forgetting distances, time, finity – everything is shiny, so wonderfully new.

Klaudia Dietewich has chosen a different approach. With documentary precision, eyes peeled to the ground, she consciously registers the characteristics of the tangible surfaces she travels on foot or by bicycle: streets and facades, asphalt and concrete, glass bricks and other materials. Most of us pay little or no attention to the ground we walk or drive on. Regardless of whether it is new or covered in potholes, light gray or pitch black, it is merely a means to an end – namely, to get us from here to there. Klaudia Dietewich, on the other hand, devotes a good deal more attention to her subject, as manifested in her photographs.

The first use of every newly resurfaced pavement or public space inevitably begins the process of erosion and damage. In the course of time, the once flawless surfaces are subjected to markings, which can be read as an archeology of the quotidian, conveying information about contemporary users and their environment. Beyond the socially critical examination, however, Klaudia Dietewich focuses on the aesthetic qualities of the easily overlooked or unheeded, translating her subjects into complex visual systems.

By no means is a street just a street, nor asphalt merely asphalt, nor is a runway just a runway in these systems. Layers have been juxtaposed, damaged surfaces have been repaired or patched, porously grainy surfaces offset reflective slickness. Road markings, the accidentally buried, the faded, and the lost give rise to a variety of tonal values and – as is the case with all that is inexpressible – an enchantingly beautiful calligraphy of the makeshift. Once we have grasped the artist’s visual language in these images, we quickly recognize the topographies from which they are taken. The often extreme close-ups of details – if we are so inclined to contemplate them – impressively reveal the apparent omnipresence of markings wherever we go. Klaudia Dietewich’s images make us conscious of these ubiquitous signs spread out so obviously beneath us, like an ongoing text.

These accidental lineaments feed our imagination with their variations and abundance of forms in unforeseen ways. Streaks, blobs, marbled washes, tears, scratches, chips, uniform mesh structures, or unruly gestural scribbles and imprints attain their highest pictorial expression, however, only after Klaudia Dietewich has subjected them to the hermetic focus of her observation – not unlike scientific specimens. In this way, she not only raises the easily overlooked or the incidental to art, divesting herself without further ado of the functionalization of materials and surfaces in the process. By completely concentrating on pure form, the commitment to line, the radiance of color, she also frees her subjects from their origins – and thus from any contextual anecdote or individual biography.

While one may concede a certain historical contamination of public spaces – after all, streets will have been traveled countless times, paths repeatedly trod – these places nevertheless must be considered of no historical importance whatsoever. Unconditionally inferring a functional context, it makes no difference whether the primary stains, planes, or hatchings were inflicted by road works. Nor does it matter that these traces delineate skid marks or the remains of a wild animal struck by a car, or signs of societally proscribed environmental destruction. In Klaudia Dietewich’s images, they have been transformed into self-referential elements of more or less nonrepresentational compositions, irresistably captivating us with their manifold associations.

In view of the many strangers, vehicles, machines, tires and rubber soles, incidents and accidents that have left their marks on areas and buildings, it is ultimately the passage of time that makes these visual treasures possible. In terms of the this oeuvre’s art historical context, parallels to social sculpture (albeit two-dimensional) come to mind; at the very least, one might speak of a quasi-participatory concept. But, on the contrary, Klaudia Dietewich’s works fascinate in their ambiguity: we cannot tell if or how much of the images were purposefully created by the artist, how much was an accident of climate or weathering, forces of nature or technology. Her ”Along the Way” series, in particular, appears not to have been authored by a human hand, thereby attain an iconic transcendence.

Even the road markings, obviously created by individuals, take on the character of timeless secret codes. At times, faded asphalt tatoos may suggest remnants of the past, or perhaps they merely impart banal instructions (measuring points, drilling sites, dimensional data, or directional arrows for road construction), whose meaning and purpose can no longer be deduced (at least by lay persons). At other times, personal watchwords – whose authors remain as nameless as their addressees – leave behind, at most, a vague idea of what was said or meant. Especially the publicly displayed proclamations usually express easily understandable and universally applicable instructions, commandments and prohibitions, significant messages, or other types of advertising.

Thus the individual fragment, character, paint dab, or line gains autonomy when the unheeded incidental is declared to be essential, even deemed predestined for depiction. Beyond the popular points of interests, which merely take us on the beaten paths of convention to the familiar, the paths and places Klaudia Dietewich has purposefully sought out and explored appear as memorials – reminding us to stop and behold, inciting both the artist and the public to continue to explore. Weaned from the familiar with respect to perspective, pace, and angle, we perceive the microscopic close-ups as exotic narrative landscapes that, in turn, appear to be fed by the diversity of shapes found in the quotidian.

The change of perspective – looking down on the planes of the ground, reversed in the camera’s view, and subsequently transformed into broad horizons during the printing process — additionally reinforces the extraordinary spatial depths characterizing these works. Initially drawn by the strong tactile-sensual qualities, the viewer is tempted to touch the smooth, rough, sandy, or metallic shimmer. The carefully selected details, vantage points, and enlargements of seemingly multilayered materials all contribute to extraordinary spacial arrangements. Unexpectedly, the close-ups of the actual subjects portrayed – compressed layers of road surfaces or water-damaged building facades – evoke a painterly panorama, seamlessly continuing the centuries’ old tradition of landscape painting. Thus lapidary levitation gives rise to naturally resistant vegetative ciphers, which throw a new light on the celestial streets and other so-called imponderabilities surrounding us.

Clemens Ottnad, Stuttgart, 2016

Aufsichten

Architektenkammer Baden-Württemberg/Stuttgart, 21. September 2010

In her invitation text to this exhibition by Klaudia Dietewich, Ladies and Gentlemen, Carmen Mundorff speaks of holiday pictures of a somewhat different kind. Please allow me to linger on this topic for a moment and ask you: Have you been away this summer, this early autumn? In the sense of: I'm off then? Have you been away? Were you on holiday?

As we all know, travelling is one of those things. It is fair to say that the last true French traveller was Henri Beyle, who wrote a number of novels under the name Stendhal, which are counted among world literature, and who travelled in the wake of Napoleon Bonaparte through, among other places, northern Italy, not least the region around Lake Como. There, where Stendhal, as an adventurer, bon vivant and kindred spirit of Goethe, went in search of clues, got to know the country and its people, visited the nobility of the region on their estates, in their villas, lived with them, lodged with them and celebrated lavish parties with them, only a few decades later, Gustave Flaubert merely visited sight after sight, ticking them off, rattling them off, in a sense "doing" Upper Italy the way we nowadays "do" South America or Australia in our summer vacations, which are no longer vacations. In short, the traveller has long been replaced by the tourist.

For some years now, of course, we have known that the beach is not only at the crowded Teutonic Grill between Rimini and Caorle, but also just around the corner, under the pavement or under the asphalt, and so it is a good thing that Klaudia Dietewich takes us by the hand with her "Aufsichten", with her photographs, and invites us to a search for traces, to a visual journey of a very special kind.

Because travelling, as the artist proves with her work, is still possible today if you want to. You just have to disregard Goethe's good old maxim "you only see what you know" and make unbiased, fresh use of your eyes, which, as an aside, is not entirely unimportant for assessing architectural questions. For ultimately, the reverse is equally true: You only know what you see or what you have seen.

But back to Klaudia Dietewich and her work. Ms Dietewich is a passionate traveller, only she does not travel as a package tourist by plane, train, ship, bus or car. Nor does she focus her gaze on the face of cities, seascapes, landscapes or on other so-called sights that one has to know as a tourist or tourist, but strictly downwards on seemingly trivial things, on what usually literally goes under the radar.

The artist is a passionate cyclist who consciously and enthusiastically exposes herself again and again to wind and weather, sun and rain, and who has already crossed half of Europe on her bicycle, from Portugal to Scandinavia and Poland. On such journeys, she looks into the face of the road, she photographs the roads she is on with her digital camera, she records road traces, deformations of the pavement, grooves, scratches, discolourations, paintings, etc., and in so doing does not really do anything other than what the first-person narrator describes at the beginning of Martin Mosebach's new, extremely readable novel as follows (and I quote): "Pursuing traces, collecting circumstantial evidence in order to form from it a picture of hidden processes, fantasising myself into hidden relationships that only come to the surface of reality in tiny shocks, that was my irresponsible and, of course, completely haphazardly pursued pleasure." (end of quote)

However, the artist does not proceed haphazardly. "Since time immemorial," says Klaudia Dietewich, "roads have been the lifelines of every society, of every civilisation. But the streets I drive along are not only functional carriers, they are above all a central arena of life. This is where encounters, collisions, accidents happen; dramas and stories play out, life itself. Streets are a mirror of life. And streets change, they wear out, they are damaged, repaired, painted, marked. Traces are found here, transient traces of human presence, snapshots that change continuously, that fade, that disappear again more or less quickly. Traces that reveal something about their originator, that tell stories and create images of the places where they were found."

The street, then, as mirror and stage, and the photographer as storyteller. La strada: It is surprising that it did not become a central theme of the visual arts much earlier. But if streets are scenes of life, lifelines in which our existence pulsates and pulsates down to the capillaries, then Klaudia Dietewich's photographic journeys by bicycle can certainly be understood as a life journey (in the literal sense) on which she traces life itself: the life of our society, of a collective, but also of countless individuals.

But being on the road is not enough. Back home, the artist then begins to edit her travel souvenirs, the digital photos, changing them by the choice of cropping and the degree of enlargement. Finally, they are transferred to metal plates. The photographic objèts trouvés are thus transformed into works of art. By transforming the seemingly banal, crude photographic finds, Ms Dietewich gives them a new quality. Reality is distanced, abstracted, patches and stains, scratches and scrawls become structures, graphic poetry emerges, which is certainly anything but meaningless.

The existential substrate, the street with all its traces of human existence and suchness, always remains implicit, and so Klaudia Dietewich's work not only invites us to take a journey in our minds, to follow traces, however inconspicuous and small; not only does the artist invite us to gather quasi-criminalistic clues so that we can form a picture of hidden processes, but, and this is perhaps the most important aspect of her work, she suggests that, like Marcel Proust, we embark on a search for lost time by exposing ourselves to the graphic traces in her images. At the same time, her photographic journeys empower us to travel through time.

Or perhaps the spark will jump directly to us and, in a second step, we will be inspired by her works - in our minds or in reality - to once again walk or drive the streets of our childhood and youth with alert eyes. Just as Proust finds lost time primarily on the faces of his acquaintances and friends destroyed by it, who have become old men, Klaudia Dietewich's photographs are also - among many other things - an exercise in the awareness of transience. For what could be more ephemeral than the face of the streets, than the traces we leave behind day in and day out on the roads of this world in encounters, pile-ups, on journeys or just on the way home: skid marks, blood, the abrasion of our tyres or the chalk we used as children in the game of heaven and hell?

So when Klaudia Dietewich ultimately focuses on the transience, the fleetingness of our life's journey and our own vulnerability, she simultaneously sharpens our eyes for the value of the moment, for the joy of existence. Her work gives us insights into ourselves. Dealing with her work gives us - as surprising as this may seem - in the words of Arthur Schopenhauer, whose 150th anniversary of death we are celebrating today, a bit of "ourselves back".

Thank you!

Dr. Jürgen Glocker, Kulturreferent Landkreis Waldshut

Der Traum vom Raum.

Klaudia Dietewich, Galerie des Wilhelm-Lehmbruck-Museums Duisburg-Rheinhausen 2015

From time to time and in the most diverse places, images force themselves into the eye, into the brain stem, into the speech centre - these images that dream of space. Of transporting people from the plane into the depths of hitherto marginalised and therefore unknown worlds, thus into the third dimension. These people should be allowed to send their eyes on a journey, to determine their own perspective, to look at the environment that is always there and yet so foreign, to let themselves be carried away by the adventure of seeing. In her photographic works, Klaudia Dietewich sets out on these visual paths, and only fundamentalists would be surprised that these take-offs into space start from such a fundamental and flat starting point: flat in the sense of low (which topographically already leads us to the run-out area of the Rhine and Ruhr), but also flat in the sense of banal.

For Klaudia Dietewich's pictorial work is initially about little more than - ground coverings. Road damage, holes and craters in urban surfaces, repair work, asphalt pigments, tar fillings. Amalgamated user surfaces for our feet and vehicles. Always so inaccurate, always patchwork, refusing any aesthetic added value, mocking any civil engineering master plan, pure aleatory. An improvisation abandoned by the idea of a system, thrown upon itself. So incalculable and makeshift, so unnoticed and fleeting, that the titles themselves still have to note the photographic jour fixe: Bochum, Hannover Colliery, 5 August 2014, 1:44 pm; Marl, Römerstraße, 8 August 2014, 2:26 pm; Duisburg, Karl Lehr Bridge, 1 August 2014, 5:40 pm. Incidental, overlooked things thus become at least an accounting statistic.

If you like, you can take the motifs of the brittle and the broken, the deformed and the makeshift patched up as relics and trace elements, as signals and indications of paths already travelled, sometimes purposefully, sometimes erroneously, soon broken off, soon redeemed. Those who like can also discover a new beauty in these motifs, namely that of the deficient, the superficial, the ephemeral, which is fed by their parallels to our human condition. If you like, you can interpret those motifs metaphorically as the transformability and need for change of life itself. Be that as it may, those interpreters of images are in any case on protected ground, for the artist's self-perception also claims her exhibited work in this or a similar way. And those who prefer pictorial history naturally call to mind the trace conservators of the modern avant-garde, whose revolutionary treatment of materials and subjects formerly remote from art has long since drawn in its own clusters of traces, from Max Ernst's frottages to the pictorial concepts of Suprematism to Jean Tinguely's Métamatics, and will probably not find an end for a long time to come in the so-called Land Art of an Andy Goldsworthy or a Richard Long. Attention has already been drawn to these parallels to Klaudia Dietewich's work in various parts of the catalogue.

If, however, the dream of space is to be imagined further, reference should now be made to the artistic design and presentation of the photograph, which in Klaudia Dietewich's work always has an aesthetic meta-level (precisely those promised by the title of the exhibition, "über wege - über reste - über tage"), a surplus and excess, as it were, and it is precisely in this that the spatialisation of the image is achieved. The camera records - in at least two senses - the motif laid on the ground floor and transfers it - adjusted in size, detail, colour and focus and bound on Alu-Dibond - to the wall, i.e. into the orthogonal. The dense hanging of objects of the same format in turn provides the scalar multiplication that now adds an applicative axis to the image discovered and taken up on the horizontal abscissa axis and opens up an entire vector space. Klaudia Dietewich also prefers to apply this principle of analytical geometry where she places the image on the upward-facing partial surface of a cube or cuboid and thus underpins it three-dimensionally. Assemblages of these pictorial bodies then mark out a road map on which the former floor rubbings are reformed as now authenticated and identity-creating landmarks and 'path pieces', where they sometimes also reveal themselves as 're-routes'.

Patchwork, wallpaper patterns, links and fragments of lived life as a multiversal event of anthropological relevance. As when the universe blows bubbles. Flat in the sense of low, flat in the sense of banal, but anything but a flat pictorial conception. One might already think of Stephen Hopkins' science fiction classic Lost in Space from 1998, although Klaudia Dietewich would certainly have her own film loops on offer: Céreste (2009), Tempelhof (2010), Café Immortale (2011) or Underground (2014).

But from the video installation back to the room installation: for her cycle Heaven and Hell, the artist even takes the motif material from the basement (or, as we say in our latitudes: underground). The result is a composition of images from the former sintering hall of the ironworks in Völten, Saarland, which went into operation in 1873 and was closed down in 1986. in Völklingen in the Saarland, the so-called Völklingen Ironworks. Sinter is formed by the crystallisation of minerals dissolved in water; in this case it is the iron oxide mixture that is formed in the steel industry when hot steel surfaces come into contact with spray water. Klaudia Dietewich choreographs these rust particles into nine ceiling-high pigment prints on translucent backlit sheets, which she arranges like the stained-glass windows of a cathedral apse. But if the Gothic cathedral was an architectural signifier of the Christian world of ideas, Klaudia Dietewich's photographic position has neither an image-logical nor a salvation-historical linearium. The narrative is entirely reserved for the rust deposit that refers to sintering itself, and thus to the production of materials; in this case, to the production of steel helmets for the German soldiers of the First World War. In artistic unity with the Bach chorale O Eternity, Thou Word of Thunder and the machine noise of the sintering hall that drowns it out, a medial synopsis develops at times that encloses the suggested church space more infernally than heavenly. But is Klaudia Dietewich really concerned with historical realism?

It just struck me that you, ladies and gentlemen, have not had anything to laugh about so far, although my exhibition opening speeches, also here in Rheinhausen, have the reputation of being humorous at times. But firstly, humour is not only comedy or mystery, but has an indispensable wishful, dreamlike, even phantasmagorical appeal, an illusionary space into which man is abducted, entangled, in which he wants to be deceived, even cheated and betrayed, perhaps in order to be able to endure real life at all; and secondly - it may yet come to something.